Statement of Purpose

The American Cleft Palate Craniofacial Association’s (ACPA) Parameters of Care (ACPA Parameters) for Evaluation and Treatment of Individuals with Cleft Lip/Palate (CL/P) and/or Other Craniofacial Differences aims to provide an up-to-date summary to help guide the care of individuals with cleft-craniofacial conditions. The document is a critical driver of ACPA’s mission to facilitate access to high quality care for individuals with CL/P and craniofacial conditions and to promote team care as the best model for cleft-craniofacial care. Although this document is intended primarily for healthcare professionals, patients, families, and other stakeholders may find the content useful for informed decision-making. ACPA will develop related resources that are tailored specifically for patients and families.

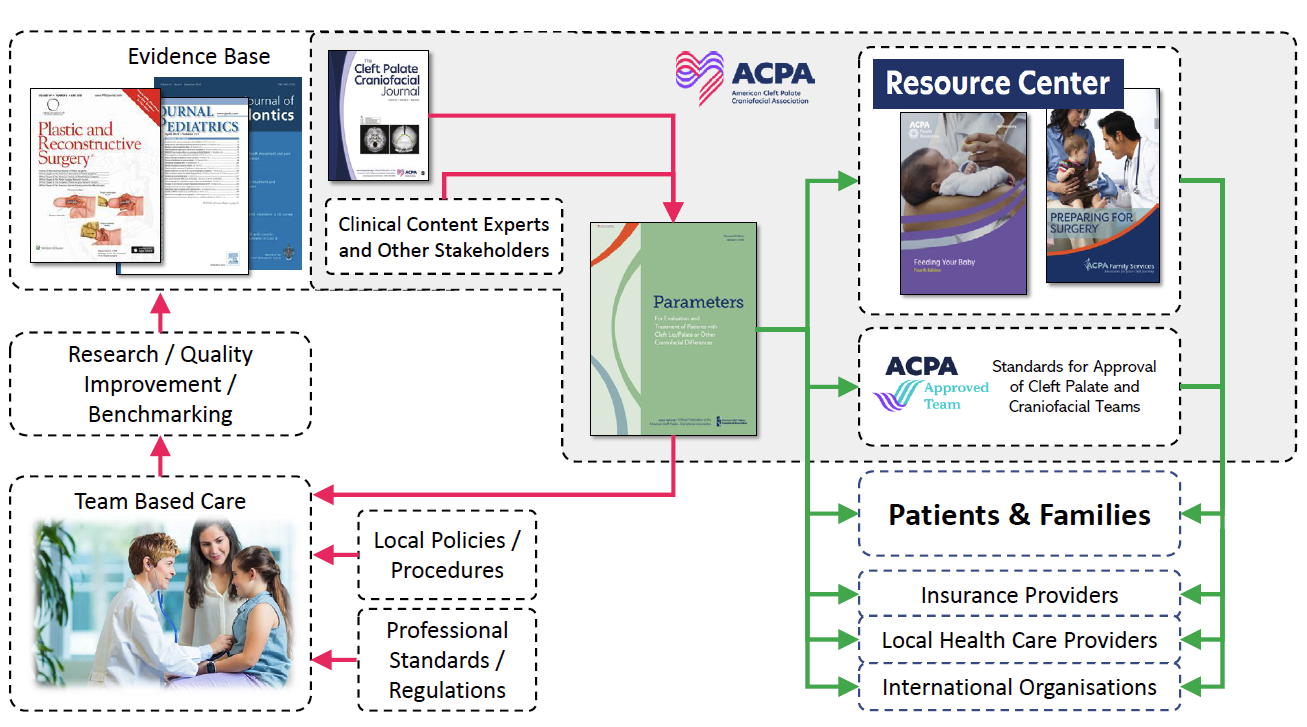

Figure 1 shows where the ACPA Parameters fit in with other ACPA resources and programs, and how they promote access to evidence-based information that informs care planning and delivery.

ACPA’s Parameters are driven by evidence-based research, including numerous studies published in the Cleft Palate Craniofacial Journal (CPCJ). They have been shaped by clinical content experts from the cleft and craniofacial fields. The ACPA Parameters provide a framework for care delivery which, in conjunction with local standards, regulations, policies, and procedures, helps inform high quality care. When this care is monitored, measured, and modified through an active quality management program (see Interdisciplinary Teams), new lines of research are identified and the evidence base for diverse aspects of care for patients with CL/P and/or other craniofacial differences is enhanced. This new knowledge will be incorporated into future iterations of the ACPA Parameters, ensuring that stakeholders can always access the best information to guide care planning and delivery. Ultimately, this information empowers stakeholders and promotes shared decision-making.

Introduction

About Cleft and Craniofacial Differences

Cleft lip, cleft palate, craniosynostosis, and conditions that affect development of the 1st and 2nd branchial arches are the most common congenital craniofacial differences. These conditions can occur in isolation or in combination with other diagnoses or syndromes. The healthcare needs of children with CL/P and/or other craniofacial differences are best managed by an interdisciplinary cleft and/or craniofacial team (see Interdisciplinary Teams). The importance of these teams is reflected in the frequency with which they are referenced throughout the ACPA Parameters. Some interdisciplinary teams focus primarily on the care of patients with CL/P, while other teams focus the care for patients with other craniofacial differences. Some interdisciplinary teams provide care for children with CL/P and other craniofacial differences.

Principles of Cleft and Craniofacial Care

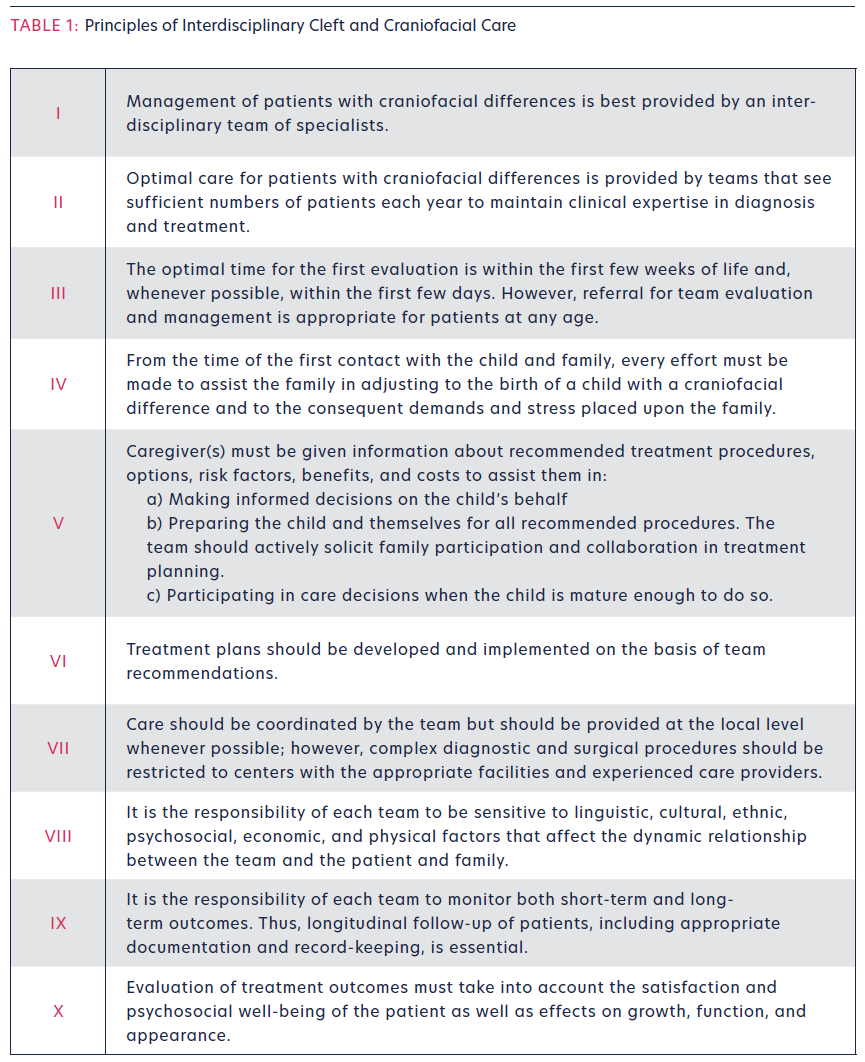

ACPA codified ten principles of interdisciplinary cleft and craniofacial care at the 1991 ACPA consensus meetings (Table 1). These principles apply to care delivery for patients with CL/P and/or other craniofacial differences regardless of the patient’s geographic location.

Relationship Between Principles and Parameters of Cleft and Craniofacial Care

The principles in Table 1 provide a broad framework under which more detailed ‘parameters of care’ are implemented. These are recommendations for the type and timing of specific elements of cleft and/or craniofacial care that care teams, patients, and families determine are appropriate as well care coordination strategies that are needed to deliver that care.

Rather than focusing on clinical disciplines (e.g. audiology, speech-language pathology, dentistry), the updated ACPA Parameters present recommendations in a problem-based context that targets optimal health and well-being. They offer detail on specific healthcare needs related to, for example, hearing, speech, and dental health. The ACPA Parameters are divided into four sections:

Interdisciplinary Teams reviews key elements of team care for patients with CL/P and other craniofacial differences. Establishing Care with the Cleft / Craniofacial Team outlines the clinical needs of neonates, including airway management, sleep, feeding, growth and nutrition and other topics. Longitudinal Evaluation and Care provides information on various components of cleft and craniofacial care after the initial contact and an initial treatment plan is established. The ACPA Parameters conclude with a description of Transition to Adult Care.